Carols, heritage, and place: Dorset in focus (Part 2 of 3)

This blog is the second of a three-part series of long-reads exploring sources of Christmas music in county record offices across southern England. Part 1 is available here.

In his novel Under the Greenwood Tree (1872/96), Thomas Hardy painted a vivid scene of preparations for Christmas carolling in the fictional parish of Mellstock, a stand-in for his home parish of Stinsford:

Shaftesbury (Dorset) in snow, 2022 (image from Dorset Live, Andrew Matthews/PA Wire)

‘Shortly after ten o’clock the singing-boys arrived at the tranter’s house, which was invariably the place of meeting, and preparations were made for the start. The older men and musicians wore thick coats, with stiff perpendicular collars, and coloured handkerchiefs wound round and round the neck till the end came to hand, over all which they just showed their ears and noses, like people looking over a wall. The remainder, stalwart ruddy men and boys, were dressed mainly in snow-white smock-frocks, embroidered upon the shoulders and breasts, in ornamental forms of hearts, diamonds, and zigzags. The cider-mug was emptied for the ninth time, the music-books were arranged, and the pieces finally decided upon.’

(‘Tranter’ is an archaic word for a carrier or trader transporting goods and/or people by horse and cart.)

While we can’t comment on the reference to cider drinking, the Music Heritage Place team has been delving into the kinds of ‘music-books’ Hardy described in his fiction. This blogpost will explore the contents of the manuscript sources, their compilers, owners, and users, and situate them within the wider Dorset carolling tradition.

Sources from Dorset History Centre

Thus far, we’ve catalogued 11 manuscripts from Dorset History Centre that contain Christmas carols:

- 2 manuscripts from the Hardy family collection (8F/163 Library 1936/75/1 and 8F/163 Fragment Mss [no shelfmark])

- 1 individual manuscript (shelfmark D-3309)

- 8 manuscripts from the Pickard-Cambridge collection (shelfmarks D-WPC/Z/2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, and 21)

The largest number of carols is found in a manuscript once owned by Stephen Arnold around 1814 (D-WPC/Z/5, with 98 carols), followed by a manuscript lacking indications of name or location (D-WPC/Z/11, with 53 carols).

D-WPC/Z/11 is something of an outlier in lacking inscriptions. Most of the other manuscripts have names and locations inscribed that offer insight into who used them, how, and where. These include: Thomas Oldfield Bartlett (1788-1841, vicar of Swanage c1810-1841), Thomas Hardy (Jr and Sr), William Cave (fl. 1805, churchwarden at Fordington), William Masters (fl. 1805, churchwarden at Fordington), Mrs Rice (fl. 1823, Puddletown), ‘the choir of Puddletown’, George Beasant (1780-1838, Puddletown), Stephen Arnold (fl. 1814), Thomas Hames of Hinton St Mary (c1769-1845) and his sons (Joel, George, and John), William Long, Annie James, and Bessie James.

Dorset History Center D-WPC/Z/2: music book, inscribed Mr William Cave & Mr William Masters Church Wardens Parish of Fordington May 1 1805’. Document held by Dorset History Centre.

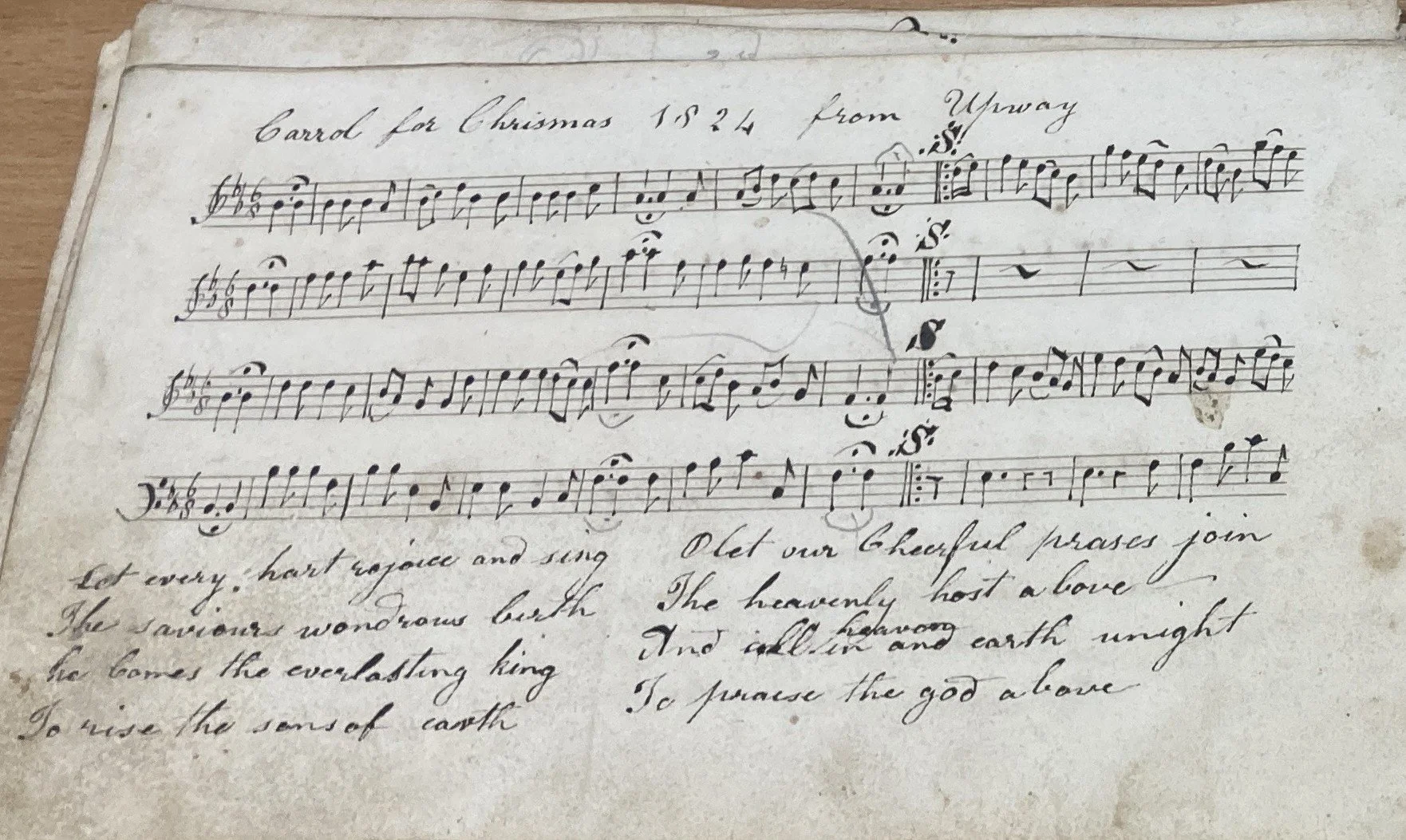

Dorset History Center D-WPC/Z/10: ‘Carrol for Christmas 1824 from Upway’. Document held by Dorset History Centre.

In addition to these names of people and places where manuscripts were made or used, there are occasional indications of where a carol may have originated. For example, one of the anonymous carol settings in D-WPC/Z/10 is titled ‘Carrol for Christmas 1824 from Upwey’ (a village just north of Weymouth). Such indications could refer to either the text or the music; but to some extent, these two aspects of a ‘carol’ can’t be separated.

Within the 11 manuscripts are 254 individual carols. Of these, only 59 are either attributed to a composer in the manuscript, or can be attributed via concordances in other sources (print or manuscript). Only 27 of the tunes (around 11 per cent) can be found in the Hymn Tune Index. You can read about some of the reasons why the Hymn Tune Index has relatively patchy coverage of Christmas carols in our previous blogpost.

In terms of attributable composers, men from Dorset are most represented. While 13 ‘carols’ by the composer Samuel Wakely (1787-1865) feature in 4 different manuscripts, ‘carols’ attributable to a named composer are generally concentrated in a single manuscript. For example, 11 of the 12 ‘carols’ attributable to Jonas Tucker feature in D-WPC/Z/11, with the attribution and year generally indicated in the title (e.g., ‘Hymn for Christmas Day By J[on]as Tucker 1827’). 7 of the 8 carols by Thomas Oldfield Bartlett are found in a manuscript from the Hardy collection (8F/163 Library 1936/75/1)), and are copied with titles following a standard format (such as ‘Christmas Carol No 5 T Bartlett 1813’).

The concentration of carols attributable to named composers in specific manuscripts is partly a reflection of how, why, and by whom the manuscripts were assembled or collected. This web of historical connections was reinforced via attempts to collect and collate Christmas carols of Dorset spearheaded by novelist Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), Richard Grosvenor Bartelot (1868-1947), vicar of the parish of Fordington in Dorset, and the composer-cum-classicist William Adair Pickard-Cambridge (1879-1957) (who deposited the Pickard-Cambridge collection at Dorset History Centre).

Collecting Christmas with ‘Dorset men’

Attempts to reconstruct historic carolling traditions in Dorset are evident in the inscriptions and correspondence by Richard Grosvenor Bartelot in manuscripts from Dorset History Centre. For example, in a 1906 note pasted into a manuscript Bartelot believed to have been copied by the composer William Knapp, he wrote that the manuscript (D-3309) ‘belonged to my Grandfather the Rev Thomas Oldf[i]eld Bartlett Rector of Swanage 1816, but it certainly was written 50 years before he was Rector of Swanage. Several of the tunes by Mr Wm Knapp the noted parish clerk + precsentor [sic] of Poole others are by Mr Wm Stounsell of Bridport + Mr Michael Wise all Dorset Men’.

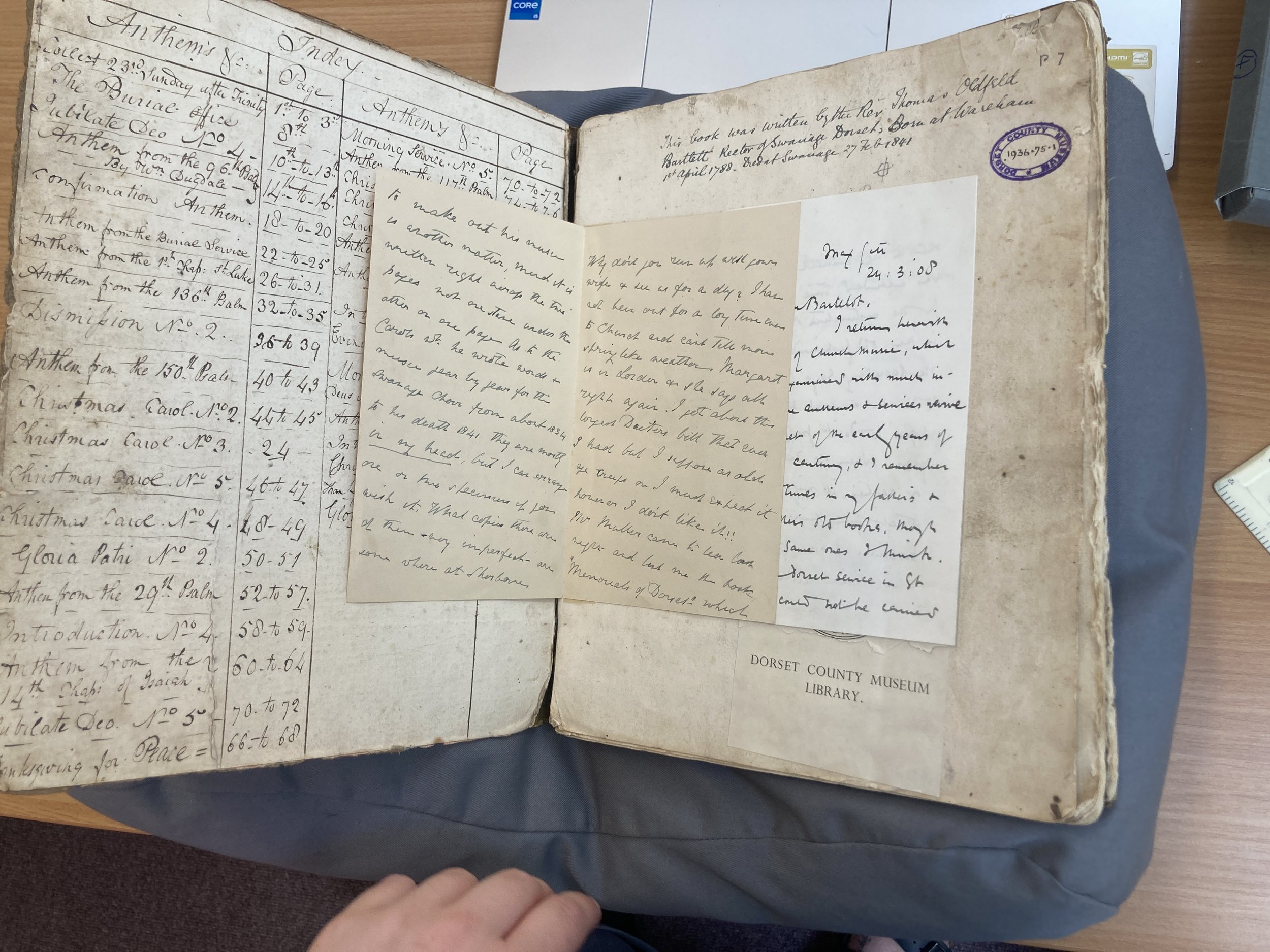

Grosvenor Bartelot’s father, Robert Leach Bartlett (b. 1827), offered further insight into ‘Dorset men’ in a letter to his son pasted into another manuscript formerly owned by his father Thomas Oldfield Bartlett (8F/163 Library 1936/75/1, from the Hardy collection). Writing from Fordington on 21 January 1908, Leach Bartlett described the manuscript as containing ‘some few Carols of about 1812 written & sung at Wareham’. He noted the manuscript also has music by William Dugdale, who ‘was an old Wareham friend of [my father] & his name you will see [above] his music.’ Leach Bartlett explained that his father ‘wrote words & music year by year for the Swanage choir’ from 1834 to 1841 are ‘mostly in my head [...]. What copies there are of them - very imperfect - are somewhere at Sherborne[.]’ He concluded by asking whether Thomas Hardy wanted ‘any of the music of old [William] Knapp Parish clerk of Poole [...] I remember a fine tune of his - “While shepherds” wch used to be sang here, but have no copies.’

8F/163 Library 1936/75/1, from the Hardy collection, front fly-leaf. Document held by Dorset History Centre.

Robert Leach Bartlett was evidently sending the manuscript for a practical purpose. Elsewhere in the letter, he wonders ‘whether your people will be able to make out [Dugdale’s] music’, as ‘it is written right across the two pages not one stave under the other’. Who ‘your people’ refers to is partly answered in a letter pasted into the very same manuscript from Thomas Hardy to Grosvenor Bartelot, dated 24 March 1908. Hardy writes:

‘I return herein the book of church music, which I have examined with much interest. The anthems & services revive old Dorset of the early years of the last century, & I remember kindred tunes in my father's & grandfather's old books, though not the same ones I think. The Dorset service in st Paul's could not be carried out in the musical portion as was intended, time not serving for the instruction of the choir in the old tunes. But the secretary says that it is to be an annual thing. They hope to do it properly next year. When the date is announced or earlier, it might be desirable to let him know of these compositions of your grandfather's, which would certainly be real Wessex music as much as Knapp's.’

Hardy’s letter clarifies that the manuscript Leach Bartlett sent to his son (Grosvenor Bartelot) and Hardy was to be used by singers in an annual ‘Dorset service’ at St Paul’s (perhaps one of the half a dozen or so parish churches under that saint’s patronage in Dorset, or perhaps even a service for Dorset expatriates at St Paul’s Cathedral in London). To Hardy, the ‘old Dorset’ revived via musical performance is the Dorset of his parents and grandparents’ generations, a Dorset he perceived as threatened by industrialisation and popular media. The music in books from the Bartlett/Bartelot family is ‘kindred’ to those of the Hardy family; and perhaps in turn, so too are the people who used it.

Frontispiece, William Adair Pickard-Cambridge, A Collection of Dorset Carols (London, 1926)

Hardy’s and Bartelot’s endeavours complemented the efforts of collectors in the 1900s to document ‘folk’ songs in rural England, particularly the southwest. At least 9 of the manuscripts discussed above come from the William Pickard-Cambridge collection. Pickard-Cambridge drew on these manuscripts when compiling his Collection of Dorset Carols (London, 1926). In the preface to this anthology he mentions titles transcribed from at least two of these manuscripts: ‘Carol by James Tucker, 1827’ (from D-WPC/Z/10) and ‘Carol by W. Townsend of Upway’(from D-WPC/Z/11). Pickard-Cambridge mistranscribed the former name, which is consistently spelled ‘Jnas’ in the manuscript, suggesting an abbreviation for ‘Jonas'.

Pickard-Cambridge’s preface further highlighted the ‘familial’ nature of this endeavour, grounded in local spaces and neighbourly relationships:

‘The following collection of Carols attempts to preserve [...] some of the best of those which for at least a century and a quarter have been sung in Dorset villages, in the manner familiar to all readers of Thomas Hardy’s novels. The nucleus of the collection is a set of eight (Nos. 1—8) given to my father, late Rector of Bloxworth, by Mr. John Skinner, parish clerk for 62 years (1817—1879). Most of these have been regularly sung at Bloxworth every Christmas at least from early in the last century till to-day, for a long period by singers under Mr. Skinner’s direction going from house to house, and since his death at an annual carol-singing held for many years at the Rectory, then at the Church and now in the parish Hall. Kind friends in many villages in the central and southern area of the county, where a like custom prevailed, have enabled me to add substantially to this nucleus, by either singing or lending me manuscript copies of the carols known to them. To all of these I am most warmly grateful.’

10 carols from Dorset Carols feature in 3 of the 11 manuscripts we’ve catalogued from Dorset History Centre. One carol from the ‘nucleus’ - ‘Awake each heart rejoice and sing’ - is copied in D-WPC/Z/11, a manuscript with no name or locations indicated. It is possible that this manuscript could be one of the sources used by the John Skinner mentioned by Pickard-Cambridge.

Later in his preface, Pickard-Cambridge explained that the phrase ‘Dorset Carol’ does not necessarily mean the music or text originated in Dorset. Emphasising the difficulty of identifying specific composers (and whether they wrote the words or tunes), he suggests that the tunes and texts were likely circulating prior to the early 19th century, and are ‘largely of the type known as “Old Methodist”’ that have ‘widely passed alike out of print (if they ever were printed)’. Pickard-Cambridge notes that the few composers he could identify ‘were not Dorset men’. This is partly true, with three tunes attributed to Thomas Clark of Canterbury, John Morton of Birmingham, a person by the surname Collins, and two tunes indicated as arrangements of music by Corelli and Handel. However, there are also three items attributed to Samuel Wakely (1787-1865), a composer who lived in Dorset for just over half of his life before moving to Hampshire at age 40.

Gender, carols, and authorship

In their writings, Hardy, Bartelot and Pickard-Cambridge viewed Dorset’s musical heritage as distinctly patrilineal, passed down by men within families and local networks. Yet female names also feature in the manuscripts in question: D-WPC/Z/6 bears an inscription on the front paste-down indicating that it was ‘The Gift of Mrs Rice to the Choir of Piddletown Feb 1st. 1823’, while D-WPC/Z/21 was in part copied by Anne and Bessie James as part of their education.

D-WPC/Z/21, ‘Mortals Rejoice’ and ‘O Happy night’, inscribed ‘Bessie James’. Elsewhere in the manuscript, Bessie has indicated where she has copied words or musical fragments by writing ‘I done this’. Document held by Dorset History Centre.

While practices varied between parishes and regions, there is ample evidence of women and girls involved in music-making at churches and chapels across England during the 18th and early 19th centuries, as singers, instrumentalists, composers, and more, including in rural parts of the southwest. So how did women and girls fit into the Dorset carolling traditions portrayed by Grosvenor Bartelot, Bartlett, and others as enacted by ‘Dorset men’ ?

We’ve yet to do a deep-dive into the primary sources concerning the demographics of parish church musicians in Dorset specifically during this period. Hardy’s recollections of carolling traditions in his fictional works are well-known, particularly his novel Under the Greenwood Tree (quoted at the start of this blogpost); while these fictional depictions often emphasise the role of men and boys, there are occasional mentions of women’s involvement. For example, in ‘Old Andrey’s Experience as a Musician’ in A Few Crusted Characters, one of the carollers pretends to play fiddle to get a meal, as he says he is ‘too old to pass as a singing boy, and too bearded to pass as a singing girl’ (the latter suggesting that girls did indeed go carolling with the choir). When their host, a ‘tall gruff old lady’, asks why he is not playing, he says he cannot play as he has a broken bow. The lady goes up to the attic and (to the pretender’s embarrassment) fetches him a new bow from among ‘some old musical instruments’.

More insight can be found by returning to Under the Greenwood Tree, in Hardy’s portrayal of Dorset men and their perception of women’s voices. Chapter 6 concerns Christmas morning at Mellstock parish church:

‘The music on Christmas mornings was frequently below the standard of church-performances at other times. The boys were sleepy from the heavy exertions of the night; the men were slightly wearied; and now, in addition to these constant reasons, there was a dampness in the atmosphere that still further aggravated the evil [...] When the singing was in progress there was suddenly discovered to be a strong and shrill reinforcement from some point, ultimately found to be the school-girls’ aisle. At every attempt it grew bolder and more distinct. At the third time of singing, these intrusive feminine voices were as mighty as those of the regular singers; in fact, the flood of sound from this quarter assumed such an individuality, that it had a time, a key, almost a tune of its own, surging upwards when the gallery plunged downwards, and the reverse.

Now this had never happened before within the memory of man. The girls, like the rest of the congregation, had always been humble and respectful followers of the gallery; singing at sixes and sevens if without gallery leaders; never interfering with the ordinances of these practised artists — having no will, union, power, or proclivity except it was given them from the established choir enthroned above them.’

The fictional parish musicians (all male) react in horror to the ‘brazen-faced hussies’ singing ‘every note as loud as we, fiddles and all, if not louder’. One musician ponders ‘what business people have to tell maidens to sing like that when they don’t sit in a gallery, and never have entered one in their lives’.

D-WPC/Z/6, front paste-down inscribed ‘The Gift of Mrs Rice of the CHoir of Puddletown Feb 1st 1823’. Document held by Dorset History Centre.

This attempt to exclude female voices is in contrast to the evidence mentioned above of women and girls being involved with the carolling and psalmody traditions of Dorset. A case in point is the music manuscript given by Mrs Rice to the choir of Puddletown parish, 4 miles away from Hardy’s home parish of Stinsford. However, it is often difficult to pin down the precise role of women and girls in musical cultures of the past, not least because so much scholarship is still dominated by investigations of composers who attributed their names to their work (who were often male, in the case of psalmody with composer attributions).

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf famously wrote: ‘I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman’. Woolf’s phrasing emphasises the subtle fluidity of enacting gender in ways that the more popular paraphrase of this quotation - ‘For most of history, Anonymous was a woman’ - erases. What it means for someone to ‘be’ an identity in the past or present is complex; the relationship of identity to ownership of something as intangible as a ‘tradition’ is equally complex. Equally, Christmas festivities are often designed to reflect the underlaying mood of the season: namely, the world being turned upside down, entrenched hierarchies overturned, and all things made topsy-turvy. Hardy, Bartelot, and Pickard-Cambridge construct the Dorset carolling tradition in a way that does embrace that chaotic fluidity to some extent, insofar as their approach is informed by an awareness of human and material mobility, subjective observation, and emotional connection. However, their notion of the Dorset musical traditions is heavily shaped by notions of heritage concerning primarily patrilineal descent and male kinship. This is not to say that their work should be disregarded, but rather that we should pursue a broader understanding of the range of people involved in music from historic Dorset, and draw from broader sources. Carolling is a collective tradition in which individual authors of text or tunes cannot be identified, arising in communities where people of all genders, ages, and backgrounds would sing collectively. It is a tradition that is inherently built on collective engagement across boundaries; namely, the physical boundary of the threshold to a home, which separates the private life of an individual or family from their wider community.

Tune in next time…

From Dorset, our next installment will move further southwest to the carols held in the Davies Gilbert collection at Kresen Kernow (Cornwall). Until then, in the words of Dorset poet William Barnes:

‘Come down to-morrow night; an' mind,

Don't leave thy fiddle-bag behind;

We'll sheake a lag, an' drink a cup

O' eale, to keep wold Chris'mas up.’

William Barnes, ‘Chris’mas Invitation’, Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect (London, 1903)

Further reading:

Clark Kimberling, ‘The Carol Books of Thomas Hardy (1778-1837) and Thomas Hardy (1811-1892)’, West Gallery Music Association (2001).

Peter Robson, ‘Under the Greenwood Tree and Beyond: Dorset church bands in Hardy’s Writings and in Real Life’, The Thomas Hardy Journal, 38 (2022), 56-73

‘The Twelve Days of Dorset Christmas’, Dorset History Centre Blog (26 December, 2022).

Our playlist:

‘Awake ye mortals all’ from the album Under the Greenwood Tree - Mellstock Band

‘Chariots’ from the album Rudolph Variations - Melrose Quartet

‘As Shepherds watched their fleecy care’ from the album The 25th - Magpie Lane

‘Hark what news the angels bring’ from the BBC Song Detectorists Cornwall episode - Melrose Quartet

This piece not only features in D-WPC/Z/5, D-WPC/Z/8, but a manuscript in Kresen Kernow (Cornwall)… check out our next blog post to learn more!