Carols, Heritage, and Place: Cornwall in focus

This blog is the third (and final) of a three-part series of long-reads exploring sources of Christmas music in county record offices across southern England. Part 1 is available here; Part 2, here.

For our final instalment this year, we’ll be exploring carols in Cornwall, a region that remains among the more isolated parts of England. This blogpost will focus on vernacular carol sources from the collection of Davies Gilbert (born Davies Giddy, 1767-1839) now held at Kresen Kernow,. It will explore two manuscripts of carol texts (DG/131 and DG/132) and two manuscripts with notated carol music (DG/92 and DG/133). It will also uncover Gilbert’s editing process for his Some Ancient Christmas Carols with the Tunes to Which They were Formerly Sung in the West of England (1st ed. 1822/2nd ed. 1823), in part drawing on evidence from bundles of proofs and manuscript scraps (DG/95 and DG/134).

Engraving of Davies Gilbert; engraved by John Thompson (1785–1866)

Davies Gilbert and the carol revival

Davies Gilbert was born to landed gentry in 1767 in St Erth, Cornwall. He mainly resided at his wife’s family estate in Eastbourne, while being a Tory MP for the ‘rotten boroughs’ of Helston and Bodmin in Cornwall from 1804 to 1832. He was a leading member of the Royal Society, serving as president from 1827 to 1830.

In 1822, he published Some Ancient Christmas Carols With the Tunes to which They Were Formerly Sung in the West of England; he published a second edition in 1823. Gilbert describes the contents as featuring:

‘Carols or Christmas songs [that] were chanted to the Tunes accompanying them, in Churches on Christmas Day, and in private houses on Christmas Eve, throughout the West of England, up to the latter part of the late [18th] century.’

Many have commented on Davies Gilbert and his Some Ancient Carols, often citing Gilbert’s work as the first of its kind. While Gilbert was among the first to purposefully collect carols from vernacular sources for the express purpose of preservation, commentary on his work often places him as a ‘saviour’ of Cornish carolling traditions. One of the exemplars of Some Ancient Carols held by Kresen Kernow contains a press-cutting from The Times, dated 24 December 1957, in which ‘a correspondent’ writes of Gilbert as a ‘versatile Cornish worthy who saved old words and tunes’. In The New Oxford Book of Carols (Oxford, 1992), Hugh Keyte and Andrew Parrott describe Gilbert (along with William Sandys) as having ‘saved the English folk carol for posterity.’ Regarding Gilbert’s publication of ‘The Lord at First did Adam Make’, Keyte and Parrott assert:

‘[...] there can be no doubt as to its [the carol’s] authenticity. There is no evidence that Gilbert, or those that assisted him, ever tampered with their musical sources; if they had, it is scarcely conceivable that they would have produced anything so outrageous [as ‘The Lord at First did Adam Make’], and performance confirms that the printed page suggests - that there is a rough, peasant musicality about the setting as a whole to which a middle-class Georgian editor could hardly aspire.’

This blogpost will show that there is, in fact, ample evidence that Gilbert ‘tampered’ with his source material (albeit more so the texts than the music). It will interrogate ideas of Gilbert as a ‘saviour’ of Cornish carolling tradition by exploring some of the sources Gilbert used in compiling Some Ancient Carols, and outlining how Gilbert edited these sources for his publication.

Sources from Kresen Kernow

The four manuscripts in Kresen Kernow explored below are not retrospective sources made by Gilbert and his associates, but vernacular manuscripts, compiled, owned, and used by a variety of men and women in Cornwall. The people involved were not of the landed class, and included labourers who, if not miners themselves, worked proximately to the mining communities they lived among.

The first text-only manuscript (DG/131) is titled ‘Henry Nicholas his book 1805’ and contains 30 carol texts in a single, calligraphic hand, presumably that of Henry Nicholas. The second text-only manuscript (DG/132) is heavily damaged, and less carefully copied.

The more carefully copied texts feature 8 complete carol texts without notation; fol. 12v features a fragment of notated music copied in pencil (two bars of G major in duple time, transcribed in the right-hand image).

The manuscript has many inscriptions, including on the title page ‘William Morley His Book of Christmas Carrolls Written December 24th 1747’, ‘Mercy Morley Dec[ember]’, and ‘John Bastard His Hand’. Elsewhere in the manuscript, inscriptions include ‘James Marley [...] I vouch for them SLk’ (fol 8v), ‘Amy Wearn her Book her hand and pen 1764’ (fol 10v), and ‘William Morley With his Hand and His Pen is a Better Writer than all of them in 1766 December’ (fol 12r). William Morley Jr appears to have re-copied the final line of one of the carols on fol 10v, as the scribe that did so is not only different from the scribe that copied the majority of the manuscript (i.e., William Morley Sr), but wrote ‘Written by William Mourly’ underneath. These inscriptions are similar to other evidence in early modern carol sources of collective interaction, often within a family.

The first notated manuscript (DG/92) is titled ‘A Book of Carols Collected for Davies Gilbert Esqr MG and JRS by John Hutchens’. The scribe who copied the title also copied the underlay and ensuing verses in the manuscript, as well as most of the titles. Comparison of text handwriting in DG/92 to a letter dated 1823 from St Erth within another manuscript discussed below (DG/133) reveals that the text scribe was probably a William Morley active c1823. This name may be connected to the William Morley who inscribed (among other things) ‘William Morley his hand and pen [...] 1766’ in the manuscript discussed above (DG/131); it is unlikely that they are the same person, as this would make for a relatively long lifespan for someone living in 18th/19th-century Cornwall.

The music in DG/92 also appears to be copied by a single scribe. Whether this was the same person as the scribe copying the text is slightly unclear; however, the text scribe has copied a musical indication - ‘solemn’ - over bar 1 of carol 30 (‘When bloody Herod reigned King’), as well as detailed instructions throughout carol 15 indicating how the carol was to be sung (to be discussed later in this post). The neat alignment of text underlay with music further suggests the text scribe also copied the music.

Wheal Alfred (near St Erth, Cornwall)

More evidence regarding the copying process can be found among the several loose papers inserted into DG/92, in a letter dated 14 June 1816 from John Morgan of St Erth to Davies Gilbert. Morgan writes that he has ‘at last procurd a person to fulfil your [Gilbert’s] request respecting the old Christmas tunes, & as he is a labouring man, perhaps I shall not be able to procure them as soon as I coud wish[.]’ Morgan continues:

‘[...]The times are extream bad since W[heal] Alfred [mine] is stopd; scarse a man (as a mine[r]) can get a days work - there were abou[t] 20 men who thought to get something by opening the ground near the old stream w[h]ere they continued as wor[king] 4 or five weeks but last spring tides the Lord of the manor paid them a visit & destroyd the whole: I may venture to say that no convicts ever work half so labourous to share 10 pman[.]’

Morgan notes at the end that he has provided the labourer he procured ‘a small book to prick the tunes in.’

The second notated manuscript (DG/133) is similar in format to DG/92, but features music set for more voices (rather than a single-voice tune). The music is usually scored with the ‘air’ (melody) in treble clef with an additional voice notated in bass clef, although some music features more voices. The text is copied by a single, consistent scribe; however, the way the music is copied is somewhat variable, making attribution of a single scribe difficult. That said, DG/133 has similar scribal consistencies to DG/92. For example, the text scribe copied rubrics such as ‘Air’ over relevant staves, and also voice indications of ‘Treble’, ‘Alto’, ‘Air’ (or Tenor), and ‘Bass’ for ‘An Anthem[...] for Christmas Day’ (Joseph Stephenson’s ‘Behold I Bring You Glad Tidings’). The music is also relatively neatly aligned with the underlay. Another scribe has gone through the manuscript in pencil, crossing out some items and re-numbering titles.

While Davies Gilbert signed the front cover of the manuscript, the title page features a large, prominent inscription reading ‘Eleanor Morgan’s Name 1816 St Erth’, with multiple smaller inscriptions of ‘Eleanor Morgan’. Gilbert later pasted an index over this title page such that the first (and largest) iteration of the name ‘Eleanor’ is partly obfuscated. The name ‘William White’ also features on the title page, copied around the largest iteration of Eleanor’s name.

Prior to this title page are 2 loose leaves; one featuring a setting of ‘God’s Dear Son without beginning’ for 3 voices in G minor, the other a text titled ‘Carrol for Christmas’ (‘God rest you merry gentleman’ [sic]). The last of these is followed by the aforementioned note from William Morley of St Erth, dated 7 May 1823:

‘Sir, Acording [sic] to your Desire I have sent you my Fathers Old Carol Book also two others are with notes set to the same[,] Hoping they will be Exceptable [sic] to you those Carols you may keep as they are of no use to me[.]’

However, on fol. 29r, the scribe that copied the underlay (or lyrics) throughout the manuscript has copied a note. It is from Robert Edyvean addressing Davies Gilbert, and reads:

‘I have sent you those (being all I can get in the Neighbouring Parishes) hoping your goodness will excuse the imperfection of the work, but should your Honour think fitting to have it corrected, and put in print; I think it would make a nice little Book, and I humbly beg your Honour would send me a copy.’

This inscription is crossed out in pencil in the same way as some of the carols in the manuscript have been crossed out.

Who did what, where, and when?

Although DG/92’s title indicates the carols were ‘collected by John Hutchens’, the manuscript was probably copied at least in part by William Morley Jr. It is possible John Hutchens copied some or all of the music, while Morley Jr. copied the text, or simply that John Hutchens was another go-between involved in the collecting process. Robert Edyvean’s note in DG/133 suggests that he was perhaps the copyist of that manuscript, or at least in charge of collecting the music and words, with Eleanor Morgan and William White at some point owning and/or using the manuscript. The note from William Morley at the start of DG/133 probably refers to other sources. ‘My Fathers Old Carol Book’ could refer to DG/132 (the manuscript of carol texts at least partially used by his father), while one of the ‘two others [...] with notes set to the same’ could be DG/92.

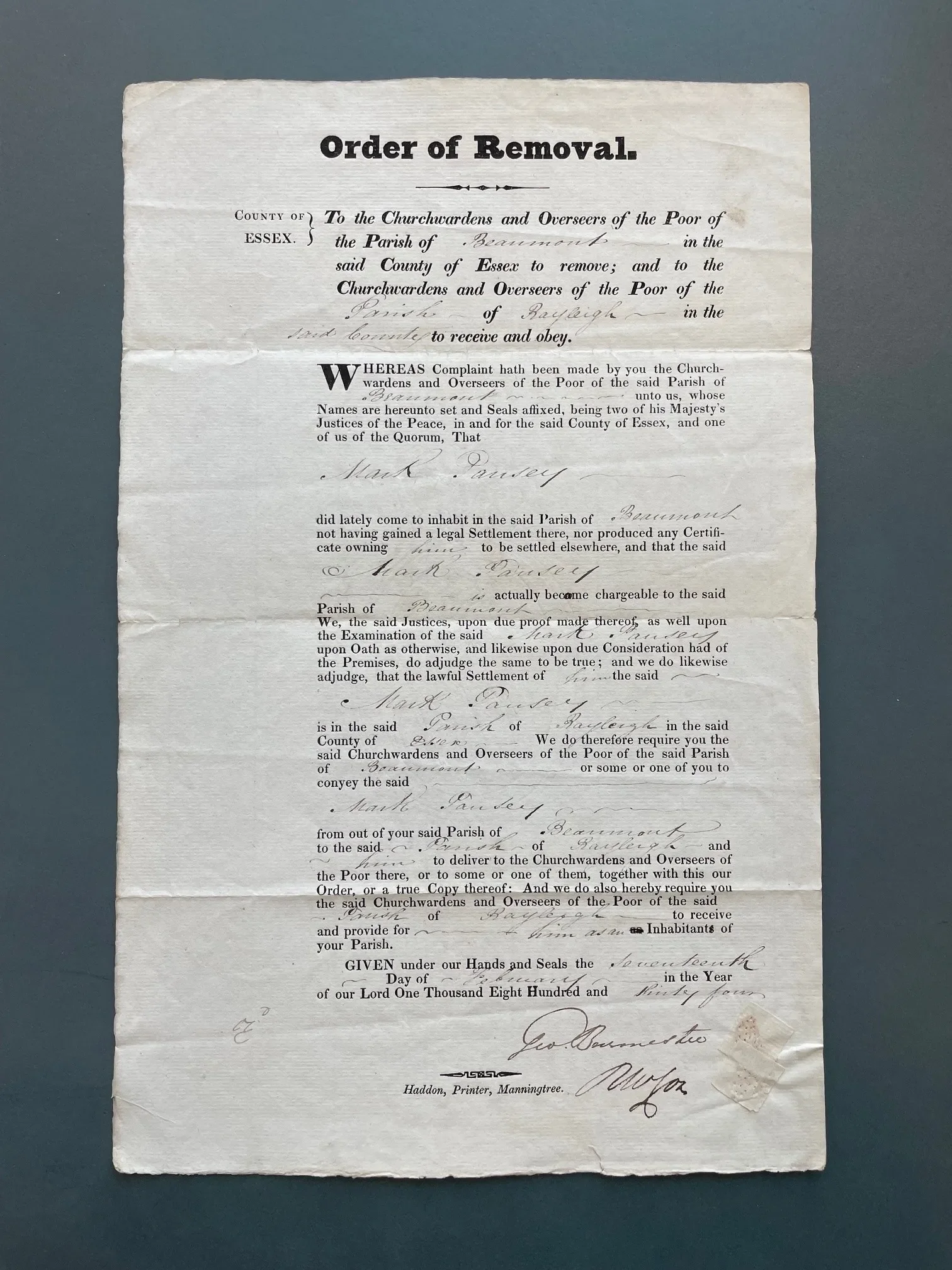

There are several mentions of ‘Robert Edyvean’ in relevant records, but the closest one in both dating and location is an entry for the quarter sessions held at Lostwithiel, dating 17 July 1817. It records an appeal by the parish of St Hilary against a removal order made 7 May 1817, which targeted Robert Edyvean, his wife Joan, and their 6 children from the parish of St Erth. Until 1834, funds for the poor were raised locally via a poor rate and distributed by the overseers of the poor. However, if overseers believed a claimant was ineligible to receive funding, the claimant would be forcibly removed from their home to another parish. This ruling could be appealed, and often was, as the parish the claimant ended up in often did not want the responsibility of maintaining impoverished or disabled people. Such was the case with Robert Edyvean, his family, and the parish of St Hilary.

The letter in DG/92 from John Morgan (likely a relative of Eleanor Morgan, of DG/133)- indicates that ‘a labourer’ collected carols ‘prick[ed] notes’ in a small book provided by Morgan. Robert Edyvean may have been this labourer, as Morgan’s letter suggests that the labourer he ‘procured’ was among many out-of-work miners in the area around St Erth and Hayle, and the aforementioned records from the quarter sessions document a Robert Edyvean as seeking poor relief in St Erth in 1817. Equally, Robert Edyvean addresses Davies Gilbert directly in his note in DG/133, indicating that he was helping collect and compile carols for Gilbert. It is also possible that John Hutchens (the name inscribed on the front of DG/92) was the ‘labourer’ collecting carols for Edyvean to give to Gilbert.

Example of a removal order, dated 1834, from Essex County Record Office (shelfmark D/P 332/13/3/90). For more about settlement papers and removal orders, check out Essex County Record Office’s blog post here.

Comparing manuscript sources to Some Ancient Carols (1822/23)

The Oxford Music Online article on carols after the Reformations describes Gilbert’s Some Ancient Carols as featuring ‘tunes drawn from oral tradition, the first of its kind’. This implies that Gilbert himself collected the tunes aurally, which as shown above was not the case; rather, he relied on a network of agents to collect manuscripts with music and texts. More importantly, however, comparison of the first and second editions with the manuscripts discussed above demonstrates that Gilbert was mainly drawing from notated sources.

The first edition of Some Ancient Carols features 8 carols with a tune and a bass line. Six of these appear to have been taken directly from the main contents of DG/133 as copied by Edyvean, with near identical ‘airs’ and bass lines. The two exceptions are ‘The Lord at First did Adam make’ (which appears in DG/133 copied by Gilbert on a folio inserted into DG/133, with no further indications as to where the words or music came from), and ‘God’s dear Son without beginning’ (also copied on a folio inserted into DG/133, also with no indication of where the music and text came from).

The musical settings in the first edition of Some Ancient Carols are more or less the same as they appear in DG/133. The main changes Gilbert makes to the tunes are adding passing notes, and turning some dotted crotchets in the bass line into plain crotchets, generally at points of cadence. The latter frequently changes the homophonic nature of cadences copied in the manuscript sources, as Gilbert does not change the dotted patterns in the tune. This results in the bass line changing note before the tune does, rather than both voices moving at the same time (as they do in the manuscripts).

Version of the carol ‘A Virgin most pure’ in DG/133 (fols 5v-6r)

Version of the carol ‘A Virgin most pure’ in Some Ancient Carols (1822), pp. 18b-18c

Gilbert also omitted many of the musical settings in the manuscripts, even for texts he did include in the publication. In one instance, this resulted in Gilbert misinterpreting (and misrepresenting) the carol in question. In the second edition of Some Ancient Carols (1823), Gilbert published the text of a carol he titled ‘In these twelve days’, which was copied with music in DG/92, but omitted the musical setting. In doing so, he seems to have ignored the careful instructions provided by the scribe (William Morley of St Erth, c1823) that indicate how the carol should be sung. This led to misordered verses, and consequently, a very different carol. Some Ancient Carols (1823) features the carol text as follows:

The carol (as Gilbert published it) finishes with the verse ‘What are these that are but twelve? What are, &c [/] Twelve Apostles Christ did Chuse [/] to preach the Gospel to the Jews.’

The verses as they appear above in Some Ancient Carols were copied in the same way in DG/92, but on the two pages after the page with the start of the carol and the musical notation and instructions.

Kresen Kernow DG/92, fol 15r. Document held by Kresen Kernow.

This first page in DG/92 shows the carol actually begins with the verse ‘what are they that are but two’. The instructions copied underneath the setting of the first verse indicate:

‘And when all the verses are gone through as above, then repeat back the answers omitting the questions, viz twelve Apostles Christ did chuse to preach the Gospel to the Jews’ and so on till you have sung “two testaments &c”.

Then “There is but one God alone in heaven above sits on his throne [/] In these twelve days and in these twelve days Let us be glad [/] For God of his power hath all things made’”.

The bottom corner inscription - ‘So that the first part that is written is the last that is sung’ refers to the next page, which has the final verse set on the lower three staves copied out at the start of the page.

The effect is similar to ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’, a carol perhaps familiar to our modern readers. Sadly, it would seem that Gilbert simply ignored this first page (with music and instructions), and simply transcribed the text straight from the ensuing pages of verses, thus missing the somewhat unique form of this carol. An interpretative edition of this carol will be made available in the new year - keep an eye out!

Gilbert also made significant changes to carol texts in both the first and second edition with changes often going beyond spelling changes to include changes to tenses, nouns, and sometimes the entire content of a verse. Gilbert’s collection in Kresen Kernow has two folders with many handwritten fragments of texts and music, as well as unbound proofs of Some Ancient Carols with annotations by Gilbert demonstrating his editing process.

For example, the carol ‘A virgin most pure’ begins in DG/133: ‘A virgin most pure as the Prophets did tell [/] should bring forth A Baby as it hath befell’. Davies Gilbert, however, has emended this text in the manuscript, changing it to ‘A virgin most pure pure as the Prophets do tell hath brought forth A Baby as it hath befell’ (the version he later published). The opening of Verse 2 in DG/133 is similarly changed from ‘In Bethlehem City in Jewry it was’ to ‘In Bethlehem in Jewry a city there was’, while in verse 5, a ‘Horse manger’ is changed to ‘an Ox manger’ (despite the fact verse 4 mentions horses and asses tied in the stable, not oxen). Another example can be found in Gilbert’s second edition, in which he published a carol text previously absent (‘Augustus Caesar having brought the world to quiet peace’). The version of this text in DG/92 has in verse 4 the line ‘Who at His Birth had then [/] an Hymn of heavenly Angels song’; Gilbert has changed this in his publication to ‘But at his birth the Host on high of Heavenly Angels sung’.

While these may seem like small changes, they are just a handful of Gilbert’s alterations. Overall these change the style and content of the scribal texts provided by Gilbert’s informants, obfuscating some of the medieval roots of these texts (as mentioned in our first blogpost).

Cribbing Cornish culture

Why so many changes? Some insight into this question can be gleaned through what Davies Gilbert’s relatives said about the musical community they were acquiring music from. The last carol text mentioned above ( ‘Augustus Caesar having brought the world to quiet peace’) was copied on one of the several inserted leaves in DG/92, and was sent with a letter from John Davy, a schoolmaster of St Just and friend of the Gilbert family. Dated 6 November 1822, it is addressed to Geoffrey John Esquire, a solicitor of Penzance and friend/colleague of Davies Gilbert. It reads:

'The foregoing [text that I copied], tho' not exactly, seems to be nearly the same as the Carol you mention; perhaps this from passing thro' plebian hands, has been much corrupted, altho' those Carols are commonly doggrel verse, and frequently contain expressions ungrammatical[,] yet not withstanding these defects, the singing or hearing them sung on Christmas Day in the Morning has often scited my feelings almost to a degree of enthusiasm.’

Given the attitudes of his peers, it is perhaps unsurprising that Gilbert reported in his second edition of Some Ancient Carols that he was ‘unsuccessful’ in getting more tunes and music from his informants. As such, he adds some other items, including a song - ‘There did 4 kings’ - which he describes as ‘esteemed by several competent judges to be a specimen of Celtic Music’. However, in a bundle of offcuts and pre-publication versions (DG/95), there is a scrap of paper with this tune (‘There did 4 kings’) copied. Gilbert wrote on the back of this scrap: ‘This tune was [copied down] by Dr. Crotch on the 4th of August 1814 from my singing it: I never heard it sung by any other than Miss Jenkin[...] The Bass [was] added by Doctor Crotch’. Dr. Crotch refers to William Crotch, a major figure in the London music scene and also Heather Professor of Music at the University of Oxford. ‘Miss Jenkin’ is probably the ‘Miss Jenkin’ mentioned in the aforementioned letter from John Morgan in May 1816, prior to Morgan discussing the troubles facing the miners. Miss Jenkin’s exact role in the origins of his song is unclear, but Gilbert makes no mention of either Miss Jenkins or William Crotch in his published version.

There are several other individuals and communities who are linked to the music and text provided to Gilbert. Sometimes they are named by Gilbert in notes to himself (as in the example of Miss Jenkins and William Crotch above), or feature among inscriptions in manuscript sources. However, all remain unacknowledged by Gilbert in Some Ancient Carols; judging from the preface, he seems more concerned with elaborating on his own reasons for publishing the collection:

‘The Editor is desirous of preserving [the carols] in their actual forms, however distorted by false grammar or by obscurities, as specimens of times now passed away, and of religious feelings superseded by others of a different cast’.

This excerpt has previously been interpreted as Gilbert exhibiting nostalgia for his childhood experiences of carolling, and expressing concern over the influence of Methodism and wider trends in Anglican musicking on the carolling tradition. However, Gilbert’s use of the phrase ‘distorted by false grammar’ is also reminiscent of the language used by John Davy, schoolmaster of St Just, to describe the carol he sent to Gilbert’s friend (Geoffrey John) as ‘much corrupted’ ‘doggrel verse’ full of ‘expressions ungrammatical’. One possible interpretation of the above excerpt is that Gilbert sought to position himself saving the carols from (in the words of Gilbert’s friend, John Davy) ‘plebian hands’; hands that were, in fact, responsible for copying the music and texts Gilbert used in his publication.

The desire by Gilbert and his ilk to remove historical materials from ‘plebian hands’ is echoed in an anecdote related by Arthur G. Langdon in 1896. Langdon transcribes from Gilbert’s pocket-book an entry on 10th December 1817, in which Gilbert notes he ‘observed a cross near Truro’, and that he had ‘for many years [...] thought of rescuing it and removing the relic’. Gilbert ‘obtained’ the cross and ‘transported’ it to his estate in Eastbourne, reportedly ‘without injury to the cross itself or any Person or thing’. Langdon then relays a story from the Canon of the church Gilbert took the cross from. When asked by the canon why he ‘carried off’ the cross. Gilbert reportedly replied that he meant to ‘“show the poor, ignorant folk that there was something bigger in the world than a flint!”’. The canon reportedly replied ‘“and thus, are we robbed!”’(Langdon, Old Cornish Crosses [Truro, 1896], p.303).

Depiction of cross removed by Gilbert and placed in his personal manor (Langdon, Old Cornish Crosses [Truro, 1896], p.309)

Davies Gilbert had long harboured contempt for ‘poor, ignorant folk’. In a speech to the House of Commons in 1807, he argued against the Parochial Schools Bill, which proposed a significant increase in funding for parish schools across England. Echoing arguments against schooling of the poor throughout the 18th century, Gilbert argued that education ‘would teach [labourers] to despise their lot in life, instead of making them good servants in agriculture and other laborious employments to which their rank in society had destined them; instead of teaching them the virtue of subordination, it would render them factious and refractory, as is evident in the manufacturing counties.’ Education ‘would enable [labourers] to read seditious pamphlets’ and ‘render them insolent to their superiors’, resulting in a parliamentary need to ‘direct the strong arm of power’ to subdue this educated underclass. He concluded by stating all laws designed to alleviate poverty should be repealed, as they resulted in ‘the labour of the industrious man [...] taxed to support the idle vagrant’ (Hansard Commons, Debated 13 June 1807, vol 9 column 799).

Gilbert is referring here to the aforementioned laws mandating parishes support impoverished parishioners. These laws made life bearable for the labourers and miners who copied, collected, collated, and perhaps even composed carols for Gilbert. Gilbert in turn used this publication to style himself as a protector of ‘relics’ of Cornish history from the ‘plebian hands’ that he had in 1807 suggested be destined to be ‘ servants in agriculture and other laborious employments’.

As noted at the start of this blogpost, Davies Gilbert and his editions of Some Ancient Carols remain influential on present-day carolling traditions. Around the same time as the first publication of The New Oxford Book of Carols in 1992, carol aficionados William E. Studwell and Dorothy Jones suggested that Gilbert’s legacy, along with that of William Sandys, meant the two men ‘in time became so closely associated with the Christmas Carol in Great Britain that it almost seemed as if carols not linked with either man were socially inferior’ (Publishing Glad Tidings: Essays on Christmas Music [Haworth Press, 1998], p.7). Studwell and Jones’s commentary is, as yet, the most critical approach to Gilbert’s legacy I have yet to find; other writings on Gilbert celebrate his work with little questioning of his editorial processes or his impact on early 19th-century Cornish communities. The sources Gilbert collected are far richer in music and texts than what he represented in his publications. So too are the communities that contributed the sources, who have remained widely unrecognised in part due to their active erasure.

To conclude this Christmas…

While there is much more that remains to be said, this three-part series has hopefully drawn attention not only to the sources for early modern Christmas carolling, but how the histories of this tradition involve different understandings of family, community, heritage, and place. These differences are part and parcel of making the traditions that enact Christmas as both a holiday and a season. The Christmas story inherently asks very fundamental questions about what ‘family’ and ‘heritage’ means. We hope this Christmas offers our readers the chance to both peacefully reflect and turn the world upside down in merry celebration - may your wassailing bowl be ever-full!

Further reading:

Richard L Green, ‘The Traditional Survival of Two Medieval Carols’, English Literary History, 7 (1940), 223-238.

Jo Buchanan, ‘Performing Cornishness: the Man Engine Pilgrimage and the ritualesque’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 30 (2024), 454-474

Liz Williams, Rough Music: Folk Customs, Transgression, and Alternative Britain (Reaktion, 2025)

Our playlist:

‘Sans Carol’ on the album Sneak’s Noyse - Maddie Prior and the Carnival Band

BBC Radio 3 ‘The Song Detectorists, episode 3: Cornwall’

‘God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen’* on the album Oy to the World - the Klezmonauts (available on Apple Music only)

*Sadly, not the unusual version copied in DG/133…