Carols, heritage, and place: an introduction (Part 1 of 3)

This blog is the first of a three-part series of long-reads exploring sources of Christmas music in county record offices across southern England.

Carolling as a singing tradition is charged with much emotional, social, and political energy. This energy reflects the many roles carols have played in communal celebrations of Christmas and other festivals over the centuries, as well as accompanying tensions between rural, urban, popular, and learned singing traditions. Carols have been variously encouraged or banned by religious officials at different points in time and in different regions. They have circulated in both print and manuscript, and have been passed down orally by families and communities over the centuries. Today’s carolling traditions feature carols that remain associated with specific villages in different English counties alongside carols produced via geographic or international exchange, as well as carols that have been mainstreamed via the publishing or broadcasting industries.

‘While Shepherds were feeding their flocks’, from the Nether Wallop bass book (Hampshire Archives 210M87/2), fols 4v-5r. Digitisation provided by Hampshire Archives (available on archive.org)

In the preface to his A Collection of Dorset Carols (London, 1926), the composer-cum-antiquarian William Adair Pickard-Cambridge declared his intent to ‘deepen and to widen the appreciation of the singularly healthy and (I believe) peculiarly English attitude towards Christmas and its story which the carols express.’ The tension between highly localised practices and a sense of a wider, national Christmas zeitgeist is simultaneously the driver and result of efforts to ‘collect’ carols from various English counties (particularly rural or less accessible regions) over the past two centuries. These collecting endeavours highlighted regional specificities as regards carolling, historicised them, and placed them within a wider patchwork of customs that constitute a ‘peculiarly English attitude towards Christmas’.

The role of Christmas carols in regional traditions could be a blogpost in itself; however, this three-part blogpost will focus on our work on sources from county record offices. The first instalment introduces definitions of Christmas carols and some of the regional patterns immediately evident in our work so far. The second instalment focuses on manuscripts from the Pickard-Cambridge and Hardy family collections now held at Dorset History Centre. The third instalment focuses on carols from the Davis Gilbert collection, held at Kresen Kernow (formerly Cornwall county record office).

‘A hevenly songe y dere wel say’, from the Selden carol book, c.1425-1450 (Oxford Bodleian Library MS. Arch. Selden. B. 26, part I; full digitisation available via Digital Bodleian)

A short overview

The ‘carol’ has generally been understood as a distinctive genre of strophic song often featuring a repeated refrain, or ‘burden’. The text is often relatively simple and direct, with frequent use of idiomatic phrases or maxims. It typically tells a story, or ruminates on a specific theme (e.g., love for a devotional figure or fear of Hell). While many carols are associated with Christmas-tide, they can be associated with other, often festive times of the year (such as Easter). The carol has origins in the medieval French Carole, a form of dance-song that made its way to England via courtly exchanges over the 12th and 13th centuries. The carol enjoyed widespread popularity in pre-Reformation England for use not only in religious devotion (particularly among Franciscan Friars), but also in secular contexts, from banquets to battlefields. The Protestant reformations of the 16th century saw new forms of carols emerge, particularly after the closure of the monasteries, with carols more targeted towards celebration outside the liturgy. Carols remained associated with planned, choreographed movement, but those movements were now often located outdoors, with singers going between homes and pubs in their local area at certain times of year to sing for their supper.

Scholarship on carols often emphasises the distinctiveness of the genre, and may seek to differentiate sub-types of carols. However, we have found that many early 19th-century sources indicate a more fluid understanding of carols, reflecting the mix of styles and genres in parish psalmody of the 1800s. Sources sometimes feature music bearing the title ‘carol’ that would not ordinarily be described as ‘Christmas carols’, but rather, as Christmastide hymns, songs, or anthems (choral music for Anglican liturgy, usually setting prose texts often from the bible). For example, a setting of the text ‘Mortals awake with angels join’ in a manuscript from Dorset History Centre is described in the source as a ‘carol’, while a setting of the same text in a manuscript from Surrey History Centre is described in the source as an ‘Anthem for Christmas Day’.

Equally, anthems are sometimes copied in sources that predominantly feature music described as ‘carols’, with the source in question used either to collect Christmas carols, or for carolling. For example, in a manuscript from Kresen Kernow (DG/133, a Cornish manuscript of carols c1810), the scribe primarily copied music to which they gave the title ‘carol’ (e.g., ‘Carol the 10th’); however, they also copied an anonymous setting of the anthem ‘Behold I bring you glad tidings’, and titled it ‘An Anthem from St Luke Chapter 2nd for Christmas Day’. Even more apparent is the interchangeability of the word ‘hymn’ and ‘carol’. Joseph Key’s setting of ‘As shepherds watched their fleecy care’ was originally published with the title ‘Carol 2’; however, it appears copied in three manuscript sources dating 1806-1826 from Hampshire Archives, twice described as a ‘carol’, and once as a ‘hymn’.

Carols from county record offices

Number of sources with music for Christmas identified in county record offices per county

The West Country has long been understood as having some of the richest carolling traditions in England. In his Christmas carols, ancient and modern (London, 1833), the carol collector William Sandys suggested that unlike other parts of England, the social tradition of carolling was ‘still kept up’ in the West Country, and particularly Cornwall, where ‘the singers going about from house to house wherever they can obtain encouragement, and, in some of the parish churches, meeting on the night of Christmas-eve and singing-in the sacred morning.’ He noted that in the West Country, it was possible to get the carols ‘frequently from the singers themselves’, or from ‘private sources, where they had long been preserved in old families’. Indeed, Sandys explained the ‘modern’ portion of his publication primarily consisted of selections from the ‘very large number of carols’ he ‘procured’ from Cornwall.

Given our project has yet to finish its cataloguing work, we can’t say exactly how many sources dating 1550-1850 with music for Christmas exist in county record offices. However, our work thus far confirms the richness of the early 19th-century carolling tradition in the West Country, particularly in Cornwall and Dorset.

We have identified 58 sources (print and manuscript) with notated music for Christmas across these record offices, primarily dating c.1810-1840, with a handful from the mid-to-late 18th century. The geographic distribution can be seen in the bar chart below.

A more granular view is gained through our catalogue records for roughly 500 individual pieces of music for Christmas that can be understood as ‘carols’. Our team does not itemise compositions within printed sources, so the total number is likely to be slightly higher. The geographical distribution of these carols confirms the significant survival of musical settings of carols from Cornwall, Dorset, and Hampshire.

It is important to note that the concentration of sources with Christmas music in Cornwall, Dorset and Hampshire record offices may not necessarily indicate more thriving Christmas carol traditions in these regions. The statistics partly reflect who was collecting historical sources with carol settings in the years 1800-1840, and for what purpose (as will be discussed in the next two blog instalments). Equally, our study only covers sources preserved in county record offices, as opposed to collections in local museums or central repositories like the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library in London. Of these approximately 500 carols, we’ve identified only 59 (around 12%) in the Hymn Tune Index (HTI) thus far. The lack of entries in HTI is partly as some items have traditionally been categorised as ‘anthems’, out of HTI’s scope. HTI also does not cover ‘carols’; however, as discussed above, the difference between a ‘Christmas hymn’ and a ‘Christmas carol’ is often less clear-cut. HTI also only covers printed sources. However, even adjusting for this, this number suggests that music used in Christmas traditions in England was often specific to particular regions.

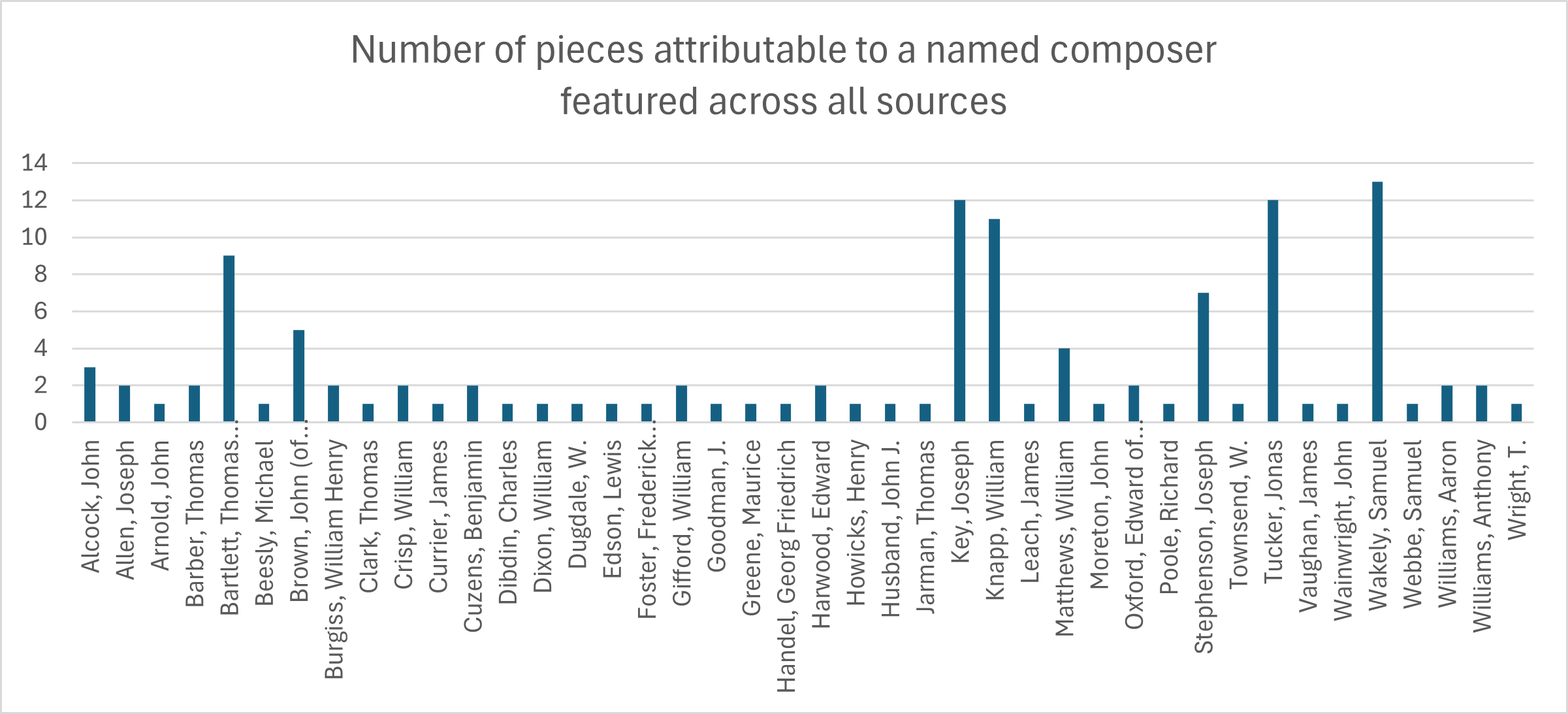

Of the 500 individual ‘carols’, 119 are either attributed in the source to a named composer, or can be attributed via concordances in other sources - print or manuscript) - with 387 yet to be attributed; in short, around 77% of ‘carol’ settings cannot yet be attributed to a named composer. Of attributed or attributable composers, ‘carols’ by Samuel Wakely, Joseph Key, and William Knapp are particularly prevalent. This is unsurprising, given they were popular composers of rural psalmody in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with their publications used across England in Anglican and non-conformist worship. While there’s still much more cataloguing to do, we can see here a wide array of composers represented in Christmas celebrations across late 18th- and early 19th-century England.

An oral or written tradition?

Carol sources often bear evidence showing interaction between oral and written practices of sharing music, as well as interactions between different singing traditions such as parish psalmody, ballad singing, and local popular traditions. For example, in the parish records of Slaugham church in West Sussex, there is a single folio with a manuscript copy of the words ‘While Shepherds watched their flocks by night’; inscribed on the front is the direction ‘For Slaugham Church Singgers [sic] Henry Martin May 27 the Ch Day 1799’, suggesting this Christmas hymn may have been sent to Slaugham from elsewhere.

There is no tune indication in the song-sheet used by the Slaugham singers; indeed, while many early modern sources of song texts have tune names indicated (with rubrics such as ‘to the tune of King John’), this is less common with the text-only sources for carols we’ve worked with. For example, there are there tune names in the carol texts collected by the antiquarian Davies Gilbert (now held in Kresen Kernow, Cornwall, to be discussed in the third blog post). The notated sources in the Davies Gilbert collection do have some texts without musical notation, but these usually indicate the tune by referring to a setting within the manuscript’ (e.g., ‘sung to carol 2’). One source of carol texts dating from the 18th century collected by Davies Gilbert has tune names, but these were added by Gilbert in the early 19th century. The source was discovered in 1940 by the medievalist Richard L. Green in Harvard University Library, and comprises one volume of carol texts ‘procured’ in 1824 for Gilbert ‘by Mr Paynter of Boskenna from Persons in the Deanery of Burian’, and two volumes belonging to one John Webbe in 1777. Green noted that Gilbert provided an index that ‘indicates those [carol texts] for which music is given in either manuscripts or printed edition[s]’. Green also noted one of the carols in the volume which did not have a tune indicated (‘Gloria Tibi Domine’) resembled medieval sources with the same text. Our team has indeed discovered a musical setting of ‘Gloria Tibi Domine’ in a manuscript from the Davies Gilbert collection in Kresen Kernow (DG/92). This suggests that just because a tune was not attributed to a carol does not mean there is no notated source for the tune available, merely that it was not highlighted by its 19th-century collectors.

Tune in next time…

We hope this post has piqued your interest in our work on carols. Our next two blog instalments will focus on specific locations, using the team’s work on carols in collections at Dorset History Centre and Kresen Kernow (Cornwall) - until then, stay warm!

Further reading:

Lisa Colton and Louise McInnes, ‘High or Low? Medieval English Carols as Part of Vernacular Culture, 1380- 1450’, in Vernacular Aesthetics in the Later Middle Ages: Politics, Performativity, and Reception from Literature to Music, ed. Katharine W. Jager (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 119-149.

Frances Eustace, Secular Carolling in Late Medieval England (Leeds: ARC Humanities Press, 2022)

Our playlist:

Arts & Ideas - New Thinking: Carols and Convents, featuring Caro Lesemann-Elliott, Micah Mckay, and Leah Broad in conversation. You can access Micah McKay’s recent doctoral thesis on carols here.

‘Make We Myrth for Crystes Byrth / The Killer Rabbit’ from the album Sing We Yule - Joglaresa

‘Glastonbury Carol’ from the album Glastonbury Carol - Gryphon